Last week I received an email from an adoption agency social worker. From what I could tell, the social worker had received a judge’s order in my case, and she was following up with a request for more information. Partly as a way of introduction, the social worker said that my case is not a normal one, and that, though it is well-documented, there are “limits that still need to be discussed.” She set out the limits and concerns generally, and then she asked me the following question:

Do you have any supporting documents that can verify that you had a relationship with your birth mother?

The irony of such a question is not lost on me, and it is probably not lost on an adoptee who has ever thought about what a birth parent relationship means, not to mention how such a relationship can be documented or proven. Put that irony aside for a moment.

The question from the social worker is, in truth, a bit more subtle. What she has really asked is whether my mother would agree to release my adoption files. That is, do I have documents to show that my mother would want me to have them? Even when I rephrase it this way and provide more context, the question still hangs in the air and lingers.

My birth mother died sixteen years ago today. I was with her when she died, with her when she took her last breath, with her and among her family—my birth family—as we watched her die at 7:07pm, March 14, 2001, at her home in south Florida. She was 54. I never forget this day, nor the days that lead up to it. And it was in these days, just before the anniversary of her death, that the social worker requested my supporting documents.

The truth is, I have thousands of these documents because, after my mother’s death, I inherited all 54 years of her life. I have dozens of her knick knacks. Hundreds of photographs. A red lobster puppet. Children’s books. Handwritten letters to her from my father, who was a teenager at the time but only a few years away from my mother’s pregnancy. I have twelve hand-written journals, beginning in 1979 and ending in 2001, just before her death, one of the last entries stating “I cannot be perfect, nor close to it.” I have her brunette wig, pages of mundane shopping lists, a small notebook with every bearing she took on a 1982 trans-Atlantic sailing trip from Denmark to St. Bart’s. In a tin box on my desk right now are three post-it notes:

God please take this fear from me

God help me have the courage and strength.

God please remove the cancer from my physical being. Help me be truly well and healthy.

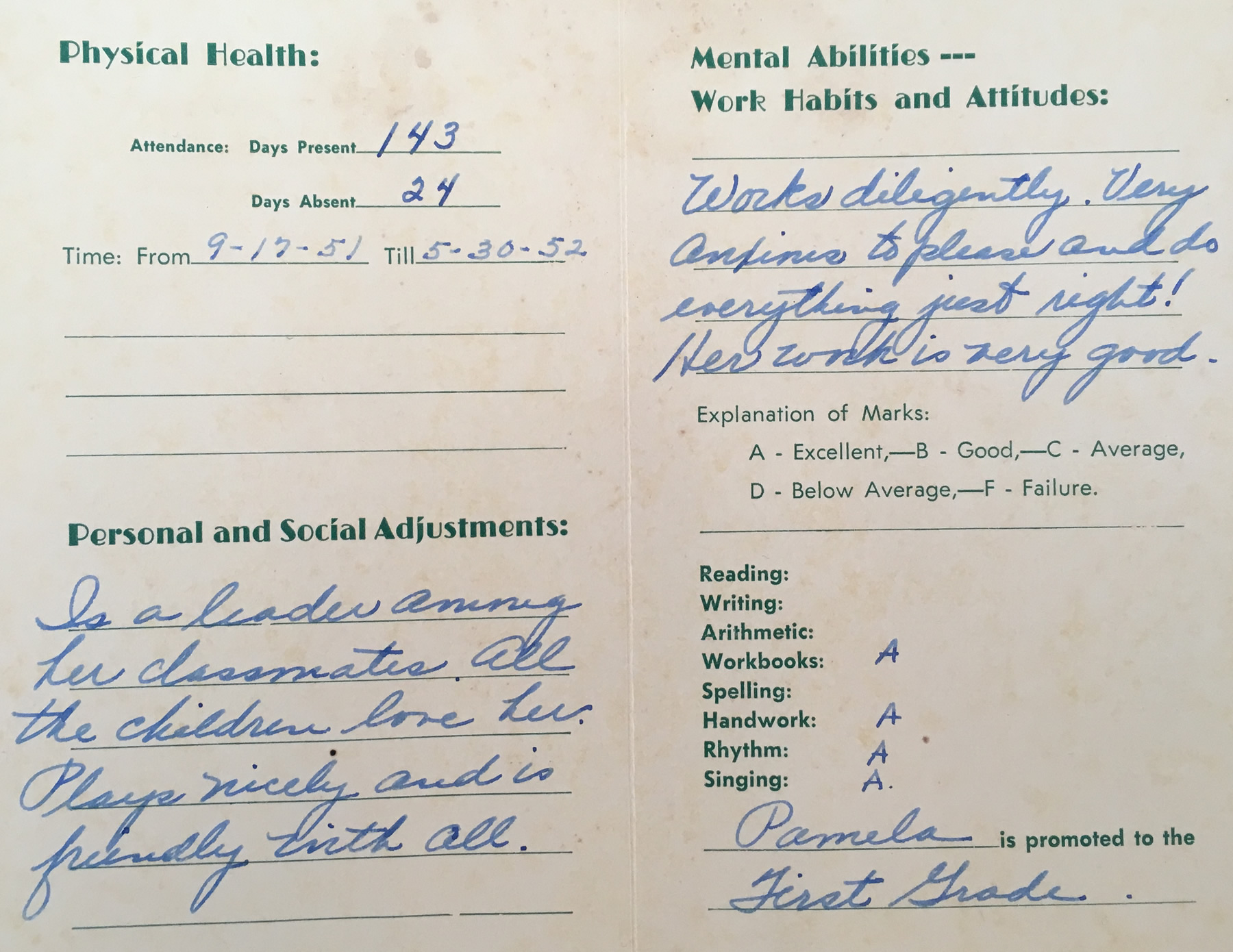

Under my desk is a box with every year of her school records, from kindergarten at the Open Air School in Florida to a master’s degree at the Rhode Island School of Design. I have all of that and more. I have it because I was her only child and, because we were close enough at the end of her life, she believed I could also be an historian and archivist, and that I could also carry on as a son.

What seems to matter now, at least what seems to matter legally, is whether I have proof to convince a judge of such a relationship. The question asked by the social worker, ordered by a judge, is really about an adoptee’s level of proof of who and what they are. It also asks a son to produce what he may still possess of a parent’s beliefs. So, in the end, what do I send? What exactly do I show?

As I tell people when they ask, I knew my mother for less than six months, which—I’m also quick to note—includes what may have been seven days with her in a Georgetown maternity home. During my life I knew that I was adopted, and I obviously knew that she existed, but I did not know who she was exactly until October 17, 2000, when I was thirty-five. She died 149 days later.

As proof of my relationship, I could send in the various details of those 149 days, few of which we were actually together. I could send in photos of us at a beach in Florida, maybe the receipt from a kayak trip near Sanibel Island. Perhaps greeting cards she sent, pictures that I sent to her, a memory of her telling me on the phone that, because of health, she had to cancel a visit to Minneapolis, where she was to see me and to meet her grandson for the first time. I could send in a copy of her obituary, where I could point to exactly what it says, right there: “She is survived by . . . her son, Gregory Luce; her grandson, Max.”

I could send in the messages she left on my voice mail, messages I still have, her voice high and the breathing slightly labored, the effect of an oxygen pump you could barely make out in the background. On one she says, “Hello, it’s mom from Florida,” and then wishes us all a happy New Year. I could digitize the one videotape I have of us, a scene from decorating a Christmas tree, me hanging the ornaments, she handing them to me because she was too tired by the end of the day to do much else. I could send in the wig that she wore. Or a photo of her without it, bald, when in the short time we knew each other it had become acceptable to see each other’s own truth.

Are any of these enough? I don’t know.

Sixteen years ago my birth mother died while sleeping under a white and pink-flowered quilt she had purchased years earlier at a New Hampshire craft fair. That quilt is now in my house, on an antique rope bed that she owned, the bed my older son now sleeps in. The quilt is his favorite blanket, and he sleeps under it and we occasionally use it for picnics. It is worn, heavy, and it is used, showing in its corners and seams threadbare evidence that it has become not only a memory but also a well-worn part of our lives.

If I could do one thing to show the agency my mother’s relationship with me, it would be this: I would fold the quilt into a square, put it carefully in a box, and send it across the country to the social worker at my adoption agency in Washington, D.C. I would also pin a note to the quilt. The note would say only this:

District of Columbia Department of Health

ATTN: Vital Records/Birth Certificates

899 North Capitol Street NE

Washington, DC 20002

Thanks for a moving account that touches many buttons for me, an adoptive parent, Greg. The first of those buttons is my regret for your mother’s passing so soon after your reunion. The second is an emotion often triggered by accounts of adoptees’ contacts with courts and adoption agencies: anger.

I feel both fairly strongly today, perhaps because I am still seething over the treatment of a recent client by the agency that handled her adoption. As you know, Minnesota law authorizes release of identifying information to adults adopted on or after August 1, 1982, provided an affidavit of non-disclosure was not filed with the agency. The law also requires that the agency obtain an affidavit from birth parents, stating they have been advised of their right to file such an affidavit.

My client was a child of the mid-80’s, born elsewhere and adopted in Minnesota. When she approached the agency one year ago, it did not tell her of her right to receive identifying information. Instead, it told her a search was required, charged her for such a search, and then refused to release the identifying information of her father when it learned he was deceased or of her mother, whom it had contacted early on.

When she came to me, the agency’s position was that it could not release the identifying information until it knew whether the birth parents had filed affidavits of non-disclosure. Obviously, no such affidavits were in the agency’s file. So, it contacted the Minnesota Department of Health, which had no such affidavits either.

It was only after I provided the agency with the statute (259.83) and it had reviewed the laws of the originating state, that it realized it could release the father’s information. Not because there was no affidavit of non-disclosure but because his death rendered the question moot under the laws of either state.

My client received the information on her father, including his obituary, on Friday, March 10, . By the time we spoke Monday morning, she had located every family member listed in her father’s obituary and her birth mother.

So much for the idea of concealing one parent’s name while the releasing the name of the other.

Ugh. Minnesota’s law is so complicated and messed up. So basically in your case the agency failed in its mandatory duty back in the ’80s to get a required affidavit from mom? And yet your client pays the price for that failure today. How much did your client spend on all this, ballpark?

I was born and adopted in Minnesota in the 1960s. My agency wanted $35 to open my file and $800 to conduct a search so that I can have my original birth certificate. I declined to give them one single penny. I declined because they have no right to hold my documents hostage. I declined because they have no right to charge me money for this. I declined because they had done an ineffectual search for my adopted brother’s birth mother to get family medical history, for which they took full payment and provided nothing. I declined because DNA testing is cheaper.

I now have the names of every one of my biological relatives out to first cousins, and quite a few beyond that. I’ve happily talked to many of them, including phone calls and group video chats. I know what I was named at birth. And still, my own original birth certificate is literally a state secret that can only be seen by employees of the state and my adoption agency, not me.

Beautiful! I do so enjoy reading what you write, Greg. Don’t give up the quilt!

$240. They asked for more for the search but my client couldn’t afford it.

Hauntingly beautiful.

Thanks. Is this TAO of theadoptedones blog? I love that blog.

Late reply…yes if you hadn’t figured it out

This is just beautiful. It’s all so surreal, adoption anomalies. Love your writing, Greg.