In the last year I have written dozens of letters to people who are unlikely to respond. I have written to Peter Pan Bus Lines, HealthPartners, the Boston Globe, New York’s municipal archives, Goucher College, the Coca Cola company, a ship’s captain, George Washington University Hospital, long-lost acquaintances, schools, old roommates, psychologists, and friends. I write to anyone I find who may be able to answer a few questions.

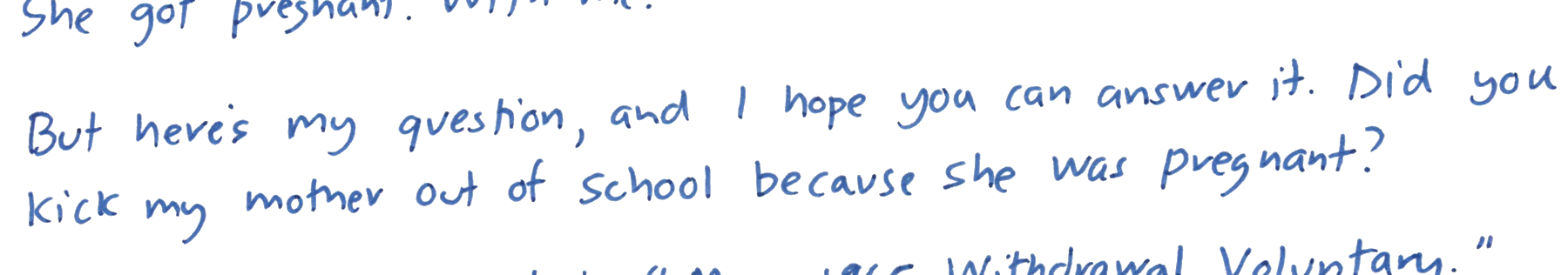

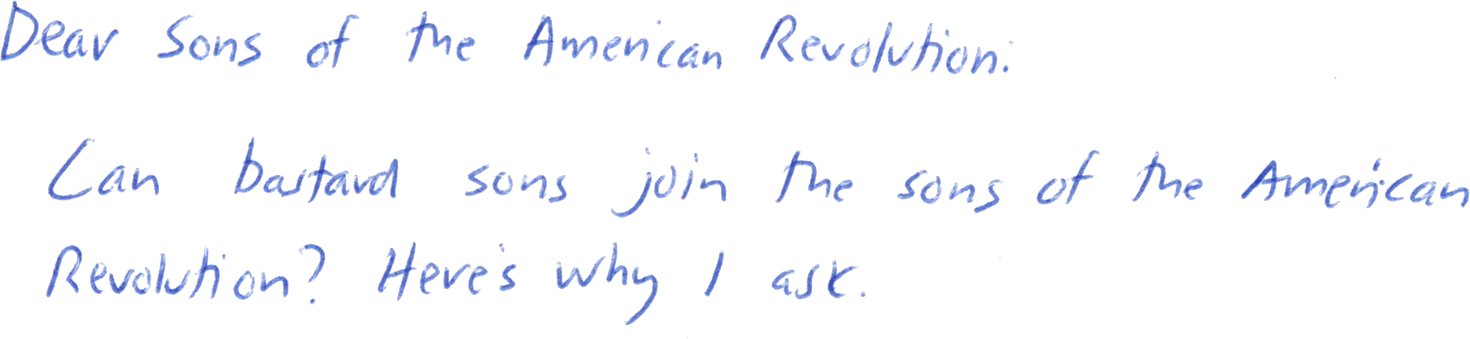

I continue to write these letters, and I often don’t know to whom I will write the next day. But in all of them, with a few exceptions, I typically want to know a single specific detail to help unravel or explain a secret. I want to know, for instance, what an unmarried woman actually did in the 1960s to determine if she was pregnant. Or what birth control, if any, a college student could access at Mount Holyoke College in 1965. Or whether a bastard like me could join the Sons of the American Revolution. Or whether Williams College held a dance on Valentine’s Day more than fifty years ago.

Why? I am adopted, and my mother found me when I was thirty-five. But it’s more complicated than that because 1) she died soon after we met; 2) I was her only child and; 3) after her death, I inherited all of her things: her records and letters and jewelry and hats and post-it notes and journals and puppets and diplomas and wedding albums. All of it. Thousands and thousands of records, hundreds of letters, the quilt she died under, the brunette wig she wore when I first met her. It has taken me fifteen emotional years to go through everything and to make sense of it all and to realize, in the end, I still had many questions. Writing my own letters is an attempt to get those questions resolved. It’s also a way to call attention to the absurdities of adoption and its long dependence on secrecy.

I compose all of my letters by hand, sometimes on cards with my name printed in orange at the top. Or with a blue ink pen on a blank sheet of white drawing paper, writing out what I want to say, usually writing it out quickly once-through, then recopying and editing it so that my handwriting is actually legible. I then transcribe it here. That is, the words in the letters I may occasionally publish here are exactly the words I physically sent there.

Without exception, I send the letters by mail. Actual blue-metal mailbox U.S. postal service mail. I keep a scanned copy of the letter for my records so that it remains part of my own story and adds to the record of my mother’s life.

My letters are often absurd. They may include private and unnecessary details, have a cheekiness suggesting detachment, and are sometimes deliberately addressed to places that existed more than fifty years ago and do not exist today. I say that here so I initially seem at least somewhat credible. In other words, I want you to know that I am well aware of what I am doing. Do I think, for instance, that a government worker at the New York Municipal Archives will respond with a crisp copy of my dead mother’s birth certificate? No, I don’t (and they didn’t, they actually sent my letter back). Do I think the plaintive “I look forward to a reply” in each letter will solicit an actual reply from, say, the Sons of the American Revolution? Not so much, but possible. Do I hope my letters get a response?

Yes. Yes, I do. I maintain such a hope, no matter how small or trivial or ludicrous that may seem.

I hope a hand-written letter with enough detail, with a wisp of mystery and shards of brutal honesty and sarcasm, will prompt a person to respond. And that response will probably not involve sitting down and writing a letter back to me. Such a thing is rare, even with people whom I know and love and to whom I send more reasonably informative hand-written letters. No, I imagine a response that is far short of a reply but may in actuality be better.

I imagine that, in response to my letters, I prompt wonder.

That wonder may be a simple “what the hell?” followed by the letter going into the trash or shredder. I acknowledge that. It is what it is. But a person’s wonder at my hand-written letter, if successful, may be slightly different, as in “Huh, this is weird.” Who is the mysterious father he writes about? When and how did he meet his mother? What happened to her? What in tarnation is he trying to find out and why are some of the things he mentions a secret?

For most of my life I carried these secrets and wonders with me. I carry these and other wonders with me to this day, and by writing letters I want other people to wonder about the secret, the mystery, the unknown details that surround my mother’s life, my birth, and the relinquishment that followed. In some ways I became exhausted with tiptoeing around the secrecy of being adopted and instead recognized the humor and absurdity of a system that continues to deny the full truth of a person’s initial existence—as well as the context and legacy of a mother’s experience. I wanted answers, and I wanted others to share my wide-eyed approach, to get others to feel that in some small way they have played and continue to play a part in a secret world that hushes things up and continues to make my origin inscrutable. Thus, I share my history with strangers even if it means that the person on the receiving end must deal with a hand-written personal letter from a guy who may seem slightly off his rocker.

As I see it, I’m first a person who wants to know what he never really knew—who his mother was, how she lived, what she became, and what happened more than fifty years ago when she left college, was shuttled to a maternity home in Washington, D.C., and then relinquished me later to a new life. Growing up I always wondered about her. From all I have, from the thousands of documents and objects and notes now scattered around my house and under my desk, this much I know: I was not always on her mind. I also know this: she never stopped wondering where I had gone.

I imagine some reactions to my letters will be that I have made things up or have exaggerated my story, that the letter is a work of fiction by some strange man who feels compelled to send larks through the mail. Fair enough, but everything I write in my letters is true, or at least provably true. And all that I am requesting are records and information that proves or bolsters that truth.

I also write letters—actual letters— because I truly like the US postal service. I love the slow life of snail mail, something that remains to this day a magical wonder. As I write this, there is a mailbox outside, about 100 feet away. I tell my children—to the point that they at times roll their eyes—that these magical blue boxes are portals that transport thoughts all over the world. I tell them that I—that you, that me, that we—can write whatever we want, package it up with paper, place a stamp on it, and send a small and beautiful self-contained package of thoughts through that magical blue box, arriving a few days later in New York, in Florida, in Martha’s Vineyard, or to a house four blocks away. Anywhere. It doesn’t matter. Fifty cents today still provides access to a magical blue box that will accept whatever you write and whatever you think and deliver it fully intact to another place. Plus you can imagine where it goes, how it gets there, and what a person at the other end must do to unwrap the surprise that has been dutifully packaged inside.

My letters are, in a tiny way, also intended to gum things up and call attention to an absurd closed adoption framework that regularly does at least two things: 1) silences adult adoptees who seek information; and 2) hides and denies the painful experiences of women who relinquished children to strangers many years ago. Adoptees like me who seek fundamental information about their origins often encounter a frustrating, calculated, and demeaning response. We approach our request for information as fully-formed respectable adults in every respect. But when we request the truth to which we should be entitled, we are told we are unreasonable and ungrateful—that we are, once again, children who do not understand what we are seeking. I understand what I am seeking. That is why I write the letters in the way that I do—bluntly, curiously, honestly and without flinching. That is why I write and ask questions like “did you kick my mother out of school because she was pregnant?”

My most recent letter is the third one I have sent to an adoption agency in Washington D.C. The first letter was returned as undeliverable because, not surprisingly, the original agency from 1965 had gone out of business and its office had long been abandoned and torn down. A second letter to its successor agency this past April was never answered, but the agency did, within a few days of getting that letter, cash the $100 check I had enclosed. Just this week I sent my third letter, asking for the same basic information—details about my adoption and a copy of the letter my mother wrote to me in 1993. In breaking from a commitment to hand-write all of my letters, for the first time I typed out a letter and sent it along through the mail. Like all my other letters, though, I’m not fully convinced the people on the other end will reply.

Greg – Thank you for another thoughtful and interesting essay. I can’t really add anything because there’s nothing to add. I understand and agree with all you’ve written.

I am going to respond to your last post about my DC Court case, but I’ll also say there that I plan to initiate a strategy to pass legislation in the District of Columbia to open adoption records. Obviously I know you’ll join the effort, but if there are other people who follow you who were born and adopted in Washington, DC, then please feel free to reach out to me directly at [email protected]. Danny Berler

Greg, did you hear back from the Sons of the American Revolution? Strange to see you mentioning that, and it gave me a little laugh. My birth mother is very active in Daughters of the American Revolution and genealogy, which i find ironic, but one of the things she told me recently upon our re-reunion was that i could join it.

Best of luck with the letters. i write a lot too, some by hand, but usually with email. i’ve had some surprising luck sometimes, but often they go unanswered. i’m not even sure the majority of them get read.

I never heard back. I’ve heard that bastards are eligible, except there’s that tiny problem of proof that you were born into a revolutionary line. In other words, you still need your original birth certificate, assuming it even has your birth father’s name on it.

Really nice piece, Greg. Remember folks like Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, AbeLincoln, and especially Eleanor Roosevelt (she received tens of thousands of them, and wrote til wee hours of the morning) loved to write letters too, without expectation. For them, it was part of their desire to connect and make a difference I think (see http://www.americanradioworks.org/segments/letters-to-and-from-eleanor-roosevelt/).

I too have written many letters, including one to Joan Hollinger, the law professor who tried to seal adoptee records almost permanently and failed. I think one empowers one’s self by writing. Through that act, I think we can change others minds the way many other forms of communications can’t, even in this era of rapid response.

I lost track of how many letters I have sent over the years. I still have one I need to write to the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, asking for just one person there to write me back in person and tell me, was it worth it to fight me for all these years and deny releasing my birth certificate, and lose, knowing you were doing the wrong thing the entire time. I don’t expect a reply when I do this. By writing, I will continue to rise above them.